(Video by Naomi Delkamiller/News21)

Catholic hospital mergers threaten access to reproductive care – even in abortion ‘safe havens’

Mergers between Catholic and secular health systems are limiting access to reproductive health care – even in states considered abortion safe havens.

Our content is free to use with appropriate credit. See the terms.

SCHENECTADY, N.Y. – He was around 8 years old when it happened.

The way Bill Levering remembers it, a relative impregnated a girl who, because of her faith, went to a Catholic hospital for care. Complications arose that might have been addressed by terminating the pregnancy, he recalls, but that was never a possibility.

“Because of the situation and because of the lack of good options, both she and the child died,” he said. “That affected me at an early stage.”

Over 60 years later, Levering watches as the joy of his life – “the redhead that is running around this room” – bounds around his home in Schenectady, New York.

His daughter, Valerie, is a bubbly toddler who was conceived through in vitro fertilization – which, Levering notes, “would not have been allowed in some circumstances.”

Rev. Bill Levering holds his daughter, Valerie, at his home in Schenectady, N.Y. Valerie was conceived via in vitro fertilization, which, along with abortion and other services, is prohibited at Catholic-run hospitals. (Photo by Morgan Casey/News21)

Valerie Norton-Levering plays on the couch with her dog, Tia. (Photo by Morgan Casey/News21)

Rev. Bill Levering, right, enjoys a moment with his wife, Abby, and daughter, Valerie. Levering and other Schenectady residents are fighting a proposed merger between a Catholic health care system and their local hospital amid worries they’ll lose access to services. (Photo by Morgan Casey/News21)

He’s referring to the ethical and religious directives that govern what health care services Catholic hospitals in the U.S. can provide.

They include bans on abortions and in vitro fertilization but also birth control, hormone therapy, vasectomies and tubal ligations – even in places like New York, where state laws aim to protect access to such care.

“The push-pull of that in my life has made me fairly committed to this idea that reproductive options need to be available for families,” Levering said.

It also drove the retired Presbyterian pastor to co-found the Schenectady Coalition for Healthcare Access – to fight a proposed merger between a Catholic health care system and his local secular hospital amid worries that residents will lose access to services.

“I agree with a lot of Roman Catholic ideas,” he said. “But I don’t want to have to worry about the religion of the people that run my hospital.”

A health care powerhouse

Catholic health care systems are some of the biggest players in U.S. health care today.

There are 665 Catholic-run hospitals across the country, according to the Catholic Health Association of the United States, and mergers between Catholic health systems and secular hospitals have been increasing.

The 10 largest Catholic health systems grew by 50% between 2001 and 2020, according to a report by health justice advocacy group Community Catalyst. And while the number of secular hospitals declined by more than 13% over that period, the number of Catholic-owned or affiliated hospitals grew by almost 30%.

These institutions are all governed by the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services, or ERDs, which are set by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.

The 70-plus rules and principles include prohibitions on care viewed as morally wrong, and if a health care system violates one, it could lose its Catholic affiliation.

“There are many good things in those directives,” said Lois Uttley, a health policy expert and former senior adviser with Community Catalyst. “But that has been overshadowed by the bishops’ incessant focus on prohibiting abortion, contraception, sterilization.”

As more and more states ban abortion following the reversal of Roe v. Wade, patients have flocked to states where the procedure remains legal. But even in those places, reproductive services may be tougher to come by because of the rise of Catholic-run health care.

“In states like New York, Oregon, Washington, Colorado, Illinois, there are large geographic regions where Catholic hospitals are the dominant provider of health care,” Uttley said. “So even though abortion is still legal in those states, there are places where it’d be hard to get one.”

Catholic health systems tend to merge with financially struggling, rural, independent community hospitals, leaving some communities with no other health care options.

In some of those places, residents have banded together to either try to stop these mergers – or push back on the idea that their hospital should have to follow the religious directives.

On and off for two years, residents of Brooklyn, Connecticut, fought a proposed merger between Day Kimball Healthcare and Catholic-run Covenant Health. The Save Day Kimball Healthcare coalition picketed, wrote letters to state officials, and got an independent analysis to examine potential impacts of the merger.

This past March, Covenant Health canceled the affiliation agreement. Day Kimball Healthcare CEO Kyle Kramer told News21 it was a business decision “not impacted or disrupted by involvement or concerns from outside groups in the public.”

Margaret Martin, a Save Day Kimball member who gets almost all her care from the institution, said she feels “incredibly relieved” – but knows the fight isn’t over.

“We know that the hospital is still wanting to find a white knight,” she said. “This is the nature of health care – of hospitals – now.”

Barriers to care

Schenectady is home to some 70,000 people about 20 miles from Albany and the once-thriving corporate headquarters of General Electric. Today, though, a quarter of the population lives below the poverty line and many are on Medicare or Medicaid.

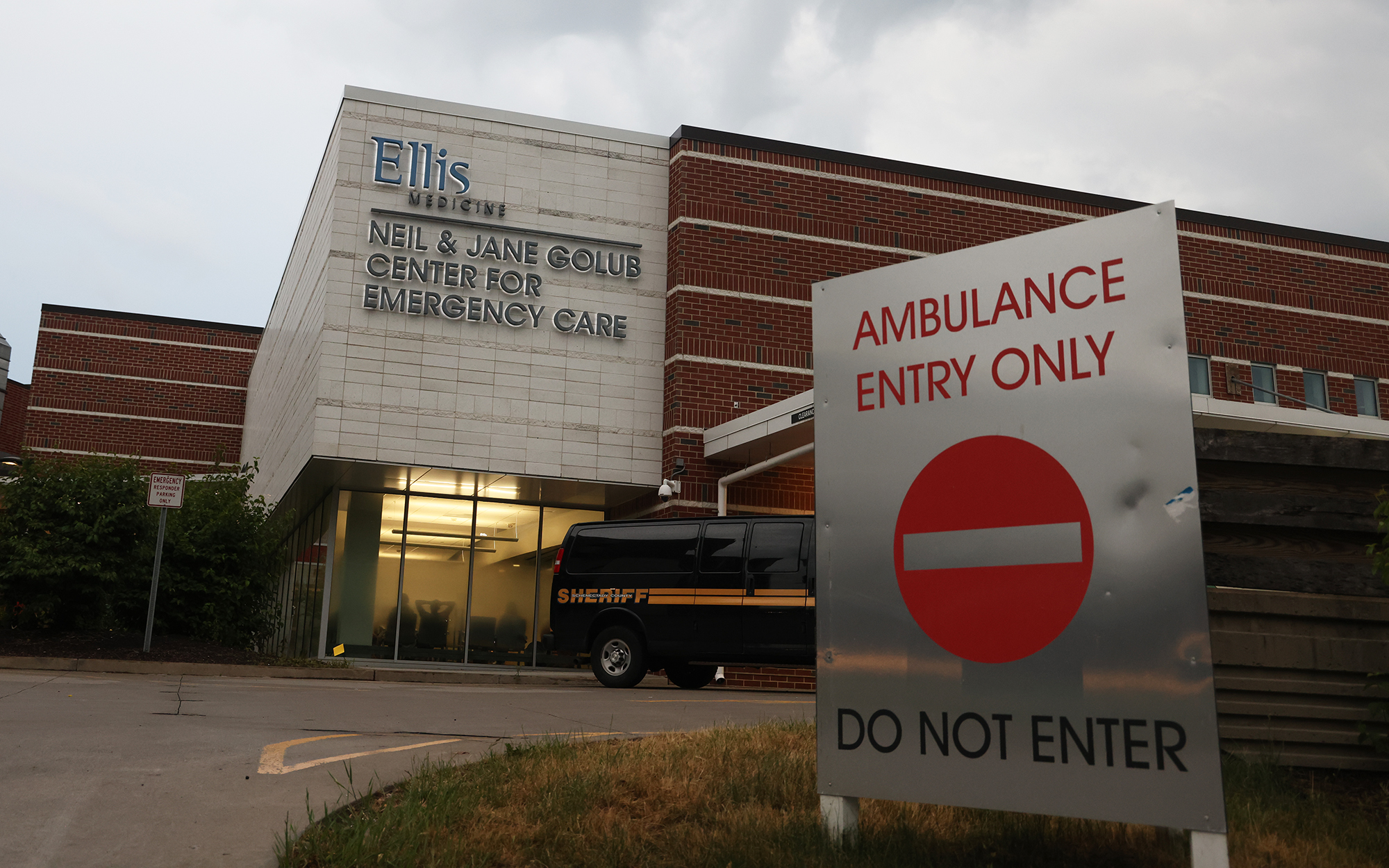

Ellis Hospital – the only inpatient hospital in all of Schenectady County – is struggling, too. Parent company Ellis Medicine has faced operational losses in the millions.

Ellis Hospital – the only inpatient hospital in all of Schenectady County – would have to abide by the ethical and religious directives that prohibit abortions and other care should a merger with St. Peter’s Health Partners become final. (Photo by Morgan Casey/News21)

Enter St. Peter’s Health Partners, which runs a chain of hospitals in this part of New York and is a member of Trinity Health, one of the nation’s largest Catholic health care systems.

In October 2020, Ellis and St. Peter’s signed a letter of intent to merge. Not long after, Levering and other Schenectady residents formed the Schenectady Coalition for Healthcare Access.

They rallied outside the county courthouse, wrote letters urging state health officials to reject the merger, and created a survey to gauge any impact on health services.

“I’m not opposed to hospital mergers. I think they’re frankly a good idea, because it cuts down on all sorts of overhead,” Levering said. “But the idea of a hospital merger that then brings in ethical and religious directives – it’s just not what we ought to be into.”

Although coalition members knew about the directives and their potential effect, most of the community did not, said Michelle Ostrelich, a Schenectady County legislator who helped start the opposition group.

“My own colleagues who are seasoned residents, who have used our health care system for many, many years, had no idea of the limitations,” she said.

Ellis Medicine CEO Paul Milton said during a 2021 City Council meeting that the merger was necessary for the hospital to stay afloat, and “St. Peter’s is our only option.” “We will have to deal with those issues that have to do with the ethical and religious directives,” he said.

A few months later, Ellis Medicine and St. Peter’s entered into a management services agreement giving St. Peter’s control over a large portion of Ellis Medicine, including all clinical departments.

The agreement says Ellis retains full legal authority over its operations – including “the ability to provide services that are prohibited by the (religious) directives.”

And yet, according to Ostrelich, St. Peter’s sent new contracts to Ellis employees that require physicians to follow the directives.

Schenectady County Legislator Michelle Ostrelich, right, talks with Jamie Crouse, director of development and marketing for the YWCA of the Greater Capital Region, during a rally on June 20, 2023, to save a birth center from closure. (Photo by Morgan Casey/News21)

“So if you go to a primary care physician who was employed by Ellis Medicine and is now employed by St. Peter’s Health Partners, they would be violating the ethical and religious directives if they give advice about birth control or anything else that’s prohibited,” she said.

Ellis Medicine declined to answer specific questions regarding the directives. But in a statement to News21, it said the agreement “increased financial and operational stability,” allowing for more beds in its adolescent inpatient mental health unit and the hiring of additional providers.

“We are committed to doing everything possible to provide quality health care for everyone in our community, and our agreement with St. Peter’s has proven to be an important part of our ongoing ability to do that,” the statement said.

St. Peter’s officials said that although services such as elective abortions and sterilizations are not permitted, “our hospitals will treat life-threatening complications in pregnancy and will save the life of the mother, even when it may result in the unintended death of the unborn child.”

“Physicians decide what procedures and care is medically appropriate based on their independent medical judgment and are expected to inform patients of all health care options, prescribe all appropriate medications, and transfer care when needed,” the company said in a statement.

Officials with the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops did not respond to several requests to discuss how the directives affect certain services. Bishop Edward Scharfenberger, whose diocese includes Schenectady, also did not respond to requests for comment.

‘We don’t do that here’

Enforcing religious directives falls to the bishops of the dioceses in which Catholic hospitals operate. The bishops act as “referees,” said Dr. Greg Burke, co-chair of the Catholic Medical Association’s ethics committee.

How strictly a bishop enforces the directives depends on the orthodoxy of their views.

“In the political world, you’ve got the far right, the far left, center, everything in between – and you will find that in the Catholic Church,” said Dr. Tim Millea, also with the Catholic Medical Association.

If a bishop determines a hospital isn’t following the directives, he can strip the hospital’s affiliation with the Catholic Church, which happened to St. Joseph’s Hospital in Phoenix after doctors performed an abortion in 2009 that they said was necessary to save the mother’s life.

Thomas Olmsted, former bishop of the Diocese of Phoenix, revoked his endorsement of the hospital as Catholic and directed its leaders to stop holding mass there. At the time, Linda Hunt, then-president of St. Joseph’s, said she and the hospital stood by its decision.

“If we are presented with a situation in which a pregnancy threatens a woman’s life, our first priority is to save both patients. If that is not possible we will always save the life we can save, and that is what we did in this case,” Hunt said in a 2010 statement. “Morally, ethically, and legally we simply cannot stand by and let someone die whose life we might be able to save.”

It is legal for Catholic health systems to deny services that are guaranteed by state laws. Since the 1970s, conscience protection laws – including the “Church Amendments” – have allowed health care providers and entities to deny care that goes against their morals.

“There are large geographic regions where Catholic hospitals are the dominant provider of health care. … Even though abortion is still legal in those states, there are places where it’d be hard to get one.”

— Lois Uttley

Former senior adviser with Community Catalyst

Daniel DiLeo, director of the Justice and Peace Studies Program at Creighton University, said bans on abortion and other reproductive care stem from Catholicism’s idea of a person’s primary and secondary rights.

“The right to bodily autonomy is legitimate,” DiLeo said. “But it is secondary relative to the more basic right to life. The right to life is the prerequisite to all other rights.”

But patients may not learn that a certain service is unavailable under the directives until they get to the hospital.

Research published in 2019 in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that 21% of Catholic hospitals in the U.S. did not explicitly disclose their Catholic identity on their websites and only 28% specified how religious affiliation might influence patient care.

“The question to ask is, ‘Who has the responsibility to disclose that information publicly?’” said Jozef Zalot, a staff ethicist at the National Catholic Bioethics Center, which advises the Catholic Church about health care and biomedical research. “Is it the Catholic institution? Is it the secular institution? Is it the government regulators?”

Dr. Corinne McLeod, an OB-GYN in New York’s capital region, said refusals to provide care also can create mental barriers for patients.

“There is a stigmatizing factor in going to your doctor, your normal OB-GYN doctor, and being like, ‘Hey, I’m eight weeks pregnant and I didn’t mean for this to happen’ … and for your doctor to go, ‘Oh well, we don’t do that here,’” McLeod said.

States like Washington and New York have considered legislation to increase transparency around mergers and denial of services.

In Washington state, Senate Bill 5241 would have required the attorney general to investigate a merger and decide whether it would decrease services, particularly reproductive, gender-affirming and end-of-life care services. The measure did not make it out of the Legislature this year.

In New York, a proposal that also remains stalled aims to require the state health department to collect and publish a list of excluded services.

“The bill has been circulating for a long time. … It’s more urgent now because of these Catholic hospital mergers,” said Melanie Trimble, chapter director of the Albany region of the New York Civil Liberties Union.

“You have the Catholic Church, which is trying very hard to basically impose their values on the way medicine is delivered in New York. And that can happen anywhere,” Trimble said. “We think our government ought to prevent that from happening.”

Few other options

In Schenectady, if services are stripped from Ellis Medicine, the burden to provide care will fall to places like Planned Parenthood. But Wendy Stark, president and CEO of Planned Parenthood of Greater New York, said their clinics can’t handle more volume because of staffing shortages.

“We’re fighting for our own survival,” she said.

Some health experts argue that abortion and other services prohibited at Catholic-run hospitals can be obtained via local Planned Parenthood clinics, like this one seen in Schenectady, N.Y., on June 18, 2023. But clinic officials say wait times are already too long. (Photo by Morgan Casey/News21)

Planned Parenthood also can’t take on complicated abortion cases or miscarriages, experts said.

“If somebody has a congenital bleeding disorder where they bleed very easily, those people are not great candidates for an outpatient surgical service,” McLeod said. “Or people who weigh a certain amount … they are not candidates for sedation in an outpatient setting. Those people need to have their procedure performed in the hospital.”

An option in that case would be Albany Medical Center, which takes 30 minutes by car or about 80 minutes via the bus, and that’s not reasonable for many, said Ostrelich, the county legislator.

“There are folks who live in Schenectady who can’t or won’t go somewhere else for their health care,” she said. “It’s either a cultural barrier, it could be other obligations – jobs, caring for other family members – that make it impossible. … Transportation itself is a big barrier.”

Dr. Rachel Flink-Bochacki, an OB-GYN in upstate New York, said other providers are prepared to care for Schenectady residents.

“But it’s absurd that they’re being forced to leave their own city and go elsewhere because the hospital in their city is refusing to provide them with appropriate health care.”

Albany Medical Center is about 30 minutes by car or 80 minutes via the bus from Schenectady but may be the closest option for complicated abortion cases or miscarriages if services are stripped from Ellis Medicine. (Photo by Naomi Delkamiller/News21)

In Schenectady, Levering, Ostrelich and Arthur Butler, a fellow coalition member, said they plan to keep fighting.

“There is a scripture that says, ‘Don’t get weary in well-doing. If you faint not, you’ll reap in due season,’” said Butler, who serves as executive director of the Schenectady County Human Rights Commission.

Butler said residents call him at the commission to say they’ve been denied certain services at Ellis. He understands the desperation patients face when care is restricted; he knew people who received underground abortions before the procedure was legal.

“I’m so used to things being taken away, rights being taken away,” Butler said. “It’s impacted me in a way that it’s made me more determined to stay in the fight.”

News21 reporters Naomi Delkamiller and Alex Appel contributed to the story.

Our content is free to use with appropriate credit. See the terms.